When it comes to working with your instinctual biases, there are two things to focus on:

- Learning to manage our reactions to them rather than being managed by them, and

- Becoming more skillful at the activities related to the three instinctual domains.

One might be tempted to think that doing one of these will automatically take care of the other, but that is not necessarily the case. Both self-management and skill building need to be worked on if we really want to become effective and well-rounded people.

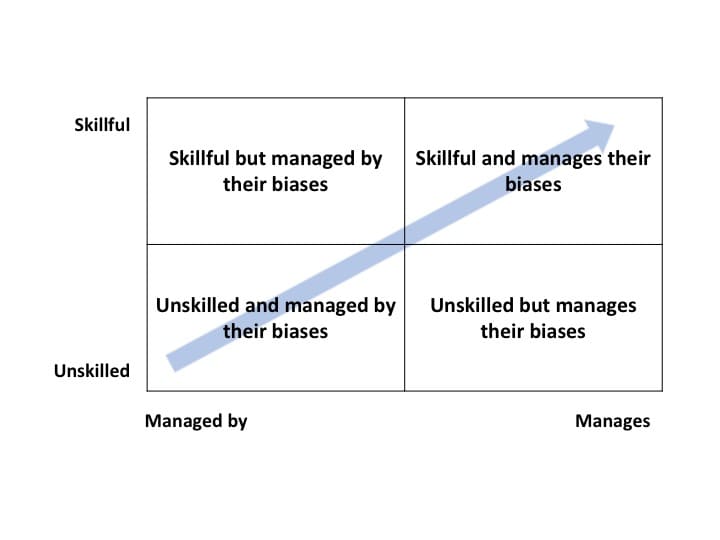

By way of understanding, we can create a simple graph where the vertical axis represents skillfulness and the horizontal axis represents the extent to which we manage our instinctual biases. The goal in our work with the biases is to move upward and to the right, represented by the arrow moving diagonally at a 45-degree angle in the diagram. Everyone’s trajectory will be different depending on whether we focus more on skillfulness or on self-management, and rarely will our progress be a straight line—there will be ups and downs. We can even move from one left to right in the course of a given day since self-management requires will and attention, both of which change based on a variety of internal and external factors. However, a trendline over time at approximately 45-degrees is the goal in working on our instinctual biases.

The three instinctual domains—Preserving, Navigating, and Transmitting—are not three discreet and singular “instincts” in the way they are often described in the Enneagram literature. Rather, they are clusters of adaptations or impulses that push us toward satisfying fundamental needs. We have to take a broad approach in working with them, recognizing that each domain contains many specific skills that can be developed, and many non-conscious impulses that we need to become more aware of and learn to manage. Thus, any chart like the one here is an oversimplification, but it helps as a guide.

To understand how to work with our biases, we’ll first describe what people look like in each of the four quadrants.

Lower Left Quadrant—Unskilled/”Managed by” their Biases

Most people live somewhere in this quadrant. People here have low self-awareness and are not aware of how their instinctual biases control their lives. The instinctual biases are, by definition, non-conscious impulses and we tend not to realize how much attention we pay to the activities related to our dominant instinctual bias and how we tend to overvalue them. Because these activities seem so natural and intuitive to us, we may not feel a strong reason to develop the ability to do them skillfully rather than intuitively. Skill in any activity requires conscious and deliberate attention, however. Someone who wants to play tennis will not become skillful at the game by just going out on the court and playing—they will take lessons, observe how more-skilled players play, and deliberately practice the basics. Every skill in life—even skills related to our instinctual biases—requires a similarly deliberate approach.

Below we describe what people of each instinctual bias tends to look like.

Preservers

Preservers in this quadrant will be very focused on preserving topics—health, safety, comfort, trying to create a feeling of order in their environment—but they will often attempt to meet these needs in ineffective or even counterproductive ways. They may frequently talk about their health and feel guilty about how well they take care of it, for example, but they won’t necessarily do the things required to be healthy. They may be obsessed with their finances but manage them poorly, or compulsively make to do lists but not follow them. They may want order but be unable to create it.*

When it comes to navigating activities, Preservers in this quadrant tend to have a combination of anxiety, guilt, and low skill, causing them to experience an awkward dichotomy in this domain. At times they will seek to avoid navigating activities if at all possible but feel guilt and shame for doing so. This guilt may cause them, at other times, to rush into these activities and actually overdo the activity, but usually in an ineffective way. They may jump into social situations but over-talk or over-commit to group activities, later regretting or even feeling embarrassed by the discomfort they felt during those interactions.

Transmitting activities will be largely ignored by Preservers in this quadrant. This means they are rarely recognized for their accomplishments and abilities at work or can struggle to make friends and build relationships in their personal lives.

Navigators

Navigators in this quadrant will be very focused navigating topics—status, identity, gossip, etc.—but act on them in ineffective or and sometimes-counterproductive ways. They may be the office gossip who can’t wait to spread both good news and bad, they may struggle to figure out their own identity in a group and feel inferior to those around them, and they may reflexively either merge with or reject the status quo or popular opinions without considering them fully.

When it comes to transmitting activities, Navigators follow the same pattern as Preservers in their secondary domain. They have anxiety, guilt, and low skill, causing them to avoid anything that might look like Transmitting most of the time, but periodically finding a sudden thirst to be noticed. In these moments they may seek attention awkwardly or inappropriately, often catching themselves in the act half-way through and withdrawing abruptly. They can look like someone who has avoided the stage for too long and feels the need to jump into the spotlight, but then finding the light too overwhelming they look for the nearest exit.

Navigators in this quadrant will largely ignore Preserving activities, sometimes leading them to be disorganized, inattentive to finances, or struggling with execution.

Transmitters

Transmitters in this quadrant will be obsessed with transmitting topics—appearance, getting what they want, leaving a lasting impression, seeking a sense of deep connection—but will often transmit ineffectively. They may dress in a way that gets noticed but leaves a poor impression; they may get what they want but alienate others along the way; they may leave an impression, but not the one they believe they left. They can also pursue deep connection with people, but may inadvertently drive those people away, choose poorly, or become bored once they do connect.

Transmitters in this quadrant will tend to lack skill and experience anxiety in the Preserving domain, often talking about preserving matters quite a bit, but not acting on them in a consistent or sustainable way. They may take on an extreme diet or exercise routine but quickly abandon it and publicly berate themselves for their shortcomings. They may attempt to commit to financial austerity that they cannot stick to. They may also become overly indulgent, insisting on having luxuries to meet their basic preserving needs.

Transmitters in this quadrant will tend to ignore the activities truly related to the Navigating domain. They may see themselves as highly “social” but be unable to see the subtle social cues and group dynamics that are happening around them or uninterested in the details of other people’s lives.

Upper-Left Quadrant—Skilled/Managed by their Biases

People with some degree of self-awareness and the ambition to work on themselves in practical ways move into this quadrant. Most of the executives I work with are here—they tend to be very skillful in their dominant instinctual domain, but they still focus (and sometimes over-focus) on it habitually. They often find themselves in the situation of having succeeded in their career based on these skills but then struggling because they over-value these skills and undervalue skills related to the other two domains. Typically, they have started to develop some skill in the second domain (frequently, even more skill than they realize) but they tend to still be weak in the third domain, often developing some kind of work-around to compensate. When people in this domain start to struggle in their careers, it is usually due to either placing too much emphasis on their skills in the dominant domain or because they under-value or lack sufficient skills in the third domain.

Preservers

Preservers in this quadrant are usually skillful in the areas related to the preserving domain—they are structured, execution-oriented, manage resources effectively, and sufficiently attend to their health and well-being. (Again, not every Preserver will be equally skilled at or attentive to every aspect of this domain.) However, they still tend to rely on the preserving domain as their comfort zone and resist stretching into the second and third domains. They usually pay some attention to skillfully negotiating the interpersonal dynamics at work and in their personal lives, but they don’t spend any more time on it than they need to. The Transmitting domain is typically still their Achilles’ heel and the area that will most likely undermine their performance because they don’t promote themselves and their accomplishments and they can become lost in the crowd at work.

Navigators

Navigators in this quadrant are typically skilled at understanding group dynamics and political trends; they nurture relationships strategically with a wide range of people and they understand group hierarchies and how to move through them effectively. They are informed about who is doing what with whom, build consensus well, and judiciously share information with the people who should have it. But they too can over-rely on this comfort zone and spend more time on navigating activities than they should, and not enough time on the activities related to the other domains. They may transmit well if it is part of their role, and may seem more dynamic and charismatic than they realize at times. The preserving domain is still usually under-developed and their inattention to details, sometimes-ineffective use of resources, and lack of structure becomes their main weaknesses.

Transmitters

Transmitters in this quadrant are often charming, charismatic, and energetic. They can get attention and use their ability to do so to further the needs of the organization, making them excellent sales people, or people who are good at inspiring, motivating, or educating others. However, their over-reliance on this domain causes them to transmit too much at times. They become effective at many aspects of execution, manage finances and resources effectively, but they can be risk-taking and overly optimistic regarding the resources that may be required for—and the potential benefit of—a project. Their vulnerability remains the Navigating domain as they struggle to see the importance of skillfully navigating group dynamics and organizational politics.

Upper-Right Quadrant—Skillful/Manages their Biases

This is where we want to get to, and it represents the ability to be self-aware enough to recognize our instinctual impulses and manage our reaction to those impulses. We see our desire to focus on the domain that feels most comfortable to us but resist its siren call and attend to whatever domain actually needs attention in a given circumstance.

As we move into this quadrant we recognize the need to consciously and deliberately build skills in all three domains, and we begin to use the right skill at the right time. It also involves recognizing when we are best served by outsourcing activities in a particular domain since it is often more effective to let more-skillful people handle important tasks when the situation allows. In this quadrant, we see our strengths and use them appropriately while recognizing our weaknesses and either working to improve or getting help when we need it.

Yes, it takes a long time to get there and consistent effort once we do. We have to clearly see our strengths and weaknesses and devote the energy required to work on relevant** weaknesses in areas that we fundamentally believe are not very important. It requires attention and discipline, like all the important things in life.

Lower-Right Quadrant—Unskilled/Manages their Biases

I’m not really sure that one could actually be in the lower-right quadrant in a consistent way since people who have the self-awareness required to manage their instinctual biases usually develop skill along the way. There are, however, people who practice a lot of self-awareness through self-help and spiritual work, but who don’t really manage themselves well or develop practical skills related to the domains. Oddly enough, these people can be the most blind to their lack of skill and self-management because they practice self-observation but don’t necessarily seek feedback, leaving them with huge blind spots. Or, they may be skillful in a few aspects of the domain but blind to most of it. Here we see that there is a difference between self-awareness, which is the ability to see ourselves, and self-management, which is the ability to control ourselves and deliberately choose our behaviors.

For our purposes, it helps to remember that the better one is at self-management, the more likely it is we will also rise in skillfulness, though arrow of progress may not be as steep as portrayed in the graph above if skill-building is not actively pursued.

Working on the Instinctual Biases

Working on moving toward the upper-right quadrant requires two activities, self-management and skill building. (For tips on developing skill in the Navigating domain, click here.

Self-management depends on three activities:

- Self-awareness—Developing deep knowledge of our habitual tendencies. This comes from self-observation, learning about the tendencies of our personality style, and seeking feedback from others.

- Attention—Practicing sufficient in-the-moment awareness to recognize when we are habitually acting or thinking in a way that is ineffective or misdirected. Learning to pay attention is enhanced when we learn to read our emotional states. Simply put, we don’t feel good when something is going wrong and our non-conscious brain will often recognize a problem before our conscious brain does. When it does, it sends us signals through our emotions—we become sad, angry, embarrassed, etc. These emotions are a signal to pay attention and see what the problem is, allowing us to redirect our thoughts or actions.

- Will—Exercising the discipline to alter our actions when it may not feel immediately satisfying to do so.

Skill-building requires that we:

- Recognize the things we need to work on.

- Learn how to do well the activities that are new to or uncomfortable for us. We can read a book, take a course, watch a video, seek advice, etc. However we learn the skills, it is important that we admit the need to learn a skill and see the value of doing so, and prioritize so we are working on the high-value skills first.

- Practice the activities we want to improve. Learning about something is not enough—no skill comes without consistent and deliberate practice. Create an action plan and follow it.

- Monitor your progress. Do whatever you have to do to hold yourself accountable. Regularly check for results and adjust your plan accordingly.

*It is important to note that because these are clusters of evolutionary adaptations rather than singular drives, we will not focus on all of the concerns in any of the domains equally. For example, one Preserver may focus much more on health and safety than on finances while another Preserver may do the opposite.

**I use the word “relevant” very purposefully. No one can be good at everything, and we shouldn’t try. Each instinctual domain is comprised of many possible specific skills—for example, the preserving domain includes activities like managing your investments, cooking, home repair, physical fitness, etc. No one has time to be highly skilled at all of them, which is why it is so important to find the right people to collaborate with so you can “outsource” certain activities and share the load. In fact, this is the advantage of being a member of a social species—we get to share the burdens as well as the fruits of our efforts. We need to be good at the activities we need to be good at and find smart alternative solutions for the others.