Enneagram "may in fact have a neurobiological basis...

there may be a biological truth beneath this fascinating system" [1].

Daniel J. Siegel, MD,

a clinical professor of psychiatry at the UCLA School of Medicine,

the author of five New York Times bestsellers

The integration of personality theories, treaties and behavior with neuroscience and human brain areas has long been a subject of fascination for researchers and practitioners alike [2-13]. This article explores the potential correlations between Enneagram types and brain specific areas (quadrants) by Katherine Benziger's brain model. The exploration of the correlations between Enneagram personality types and specific brain areas, as proposed by the Benziger brain model, provides a unique intersection of psychology and neuroscience. Understanding how Enneagram types relate to brain areas can enhance future comprehension of human behavior and mental processes.

We would like to start, that by world-renowned Enneagram authors and schools:

- “This is one area where most all of the major Enneagram authors agree—we are born with a dominant type” [14],

- “Enneagram shows us that these adaptive strategies are different based on our inborn personality type” [15],

- “While our type seems to be mainly inborn, the result of hereditary and prenatal factors including genetic patterning, our early childhood environment is the major factor in determining at which Level of Development we function” [16].

This is very close to Carl Jung’s idea, who wrote many years ago: “Ultimately, it must be the individual disposition which decides whether the child will belong to this or that type despite the constancy of external conditions” [17].

At the same time, basing on the two classical books by Don Riso and Russ Hudson [18, 19], we have the following:

- Type 1 and Type 5 both correspond to Jungian thinking types, Type 3 also corresponds to Jungian thinking types (although technically there is no direct Jungian correlation)

- Type 2 and Type 6 both correspond to Jungian feeling types,

- Type 4 and Type 8 both correspond to Jungian intuitive types,

- Type 7 and Type 9 both correspond to Jungian sensation

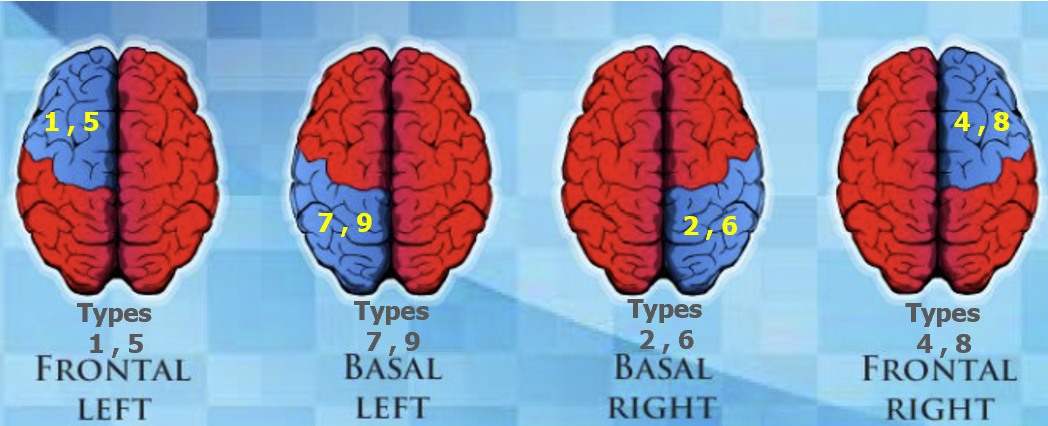

In accordance with Benziger [20], the cortex of the human brain has 4 quadrants, and the dominance of a quadrant determines a type of specialized thinking, with its unique and exclusive way of perceiving the world and processing information. Every person has one of these quadrants as dominant, a type of dominant thinking, which is naturally more efficient. So, by Benziger’s model the brain has four specialized areas – Frontal Left, Frontal Right, Basal Left and Basal Right. Each is responsible for different brain functions (which imply strengths, behavior and thinking style) and each of the Jungian functions (thinking, feeling, intuitive and sensation) corresponds to one dominant brain area of these four specialized areas following way [21]:

- Jungian thinking function - Frontal Left brain area,

- Jungian feeling function - Basal Right brain area.

- Jungian intuitive function - Frontal Right brain area,

- Jungian sensation function - Basal Left brain area,

So, taking into account the above correlations between Enneagram types and Jungian types (Jungian functions), and between Jungian functions and brain areas by Benziger’s model we can conclude that:

- Type 1 and Type 5 correspond to Frontal Left brain area,

- Type 2 and Type 6 correspond to Basal Right brain area,

- Type 4 and Type 8 correspond to Frontal Right brain area,

- Type 7 and Type 9 correspond to Basal Left brain area,

The same correlations we can find in Dr. Taylor’s article [22]. At the same time, we can see that Type 3 lacks a direct correlation with a specific brain area in the Benziger's model. It may indicate a more complex interplay of multiple regions rather than a singular focus, reflecting in this case the multifaceted nature of extraversion and achievement motivation, which Type 3 has.

Resuming all above, we can represent these connections Enneagram types with Jungian types and brain areas (quadrants by Benziger’s model) in the following table:

|

Enneagram Type |

Jungian Function

(Jungian Type) |

Brain area

(quadrant by Benziger) |

|

Type 1 |

Thinking Function (Extroverted Thinking Type) |

Frontal Left |

|

Type 2 |

Feeling Function (Extroverted Feeling Type) |

Basal Right |

|

Type 3 |

- |

- |

|

Type 4 |

Intuitive Function (Introverted Intuitive Type) |

Frontal Right |

|

Type 5 |

Thinking Function

(Introverted Thinking Type) |

Frontal Left |

|

Type 6 |

Feeling Function (Introverted Feeling Type) |

Basal Right |

|

Type 7 |

Sensation Function (Extroverted Sensation Type) |

Basal Left |

|

Type 8 |

Intuitive Function (Extroverted Intuitive Type) |

Frontal Right |

| Type 9 | Sensation Function

(Introverted Sensation Type) |

Basal Left |

In conclusion, we hope that the correlations between Enneagram types and specific brain areas according to the Benziger's brain model will provide valuable insights into the interplay between personality and brain function. Each Enneagram type exhibits distinct characteristics that align with specific brain regions, highlighting the complexity of human behavior and the neurological underpinnings that inform it. Understanding these connections can enhance our comprehension of personality dynamics and inform therapeutic approaches that consider both psychological and neurological factors.

Literature

[1] Siegel, D. J. (2010). The Mindful Therapist, A Clinician’s Guide to Mindsight and Neural Integration. W. W. Norton & Company, p. 157.

[2] Killen, J. (2009). Toward the neurobiology of the Enneagram. The Enneagram Journal.

[3] Vallander, S. (2023). A Neuroscientific View on the Enneagram of Personality. OSF Preprints. June 30. doi:10.31219/osf.io/ck79p.

[4] Vallander, S. (2023). The Enneagram and Myers-Briggs Within a Neuroscientific Framework. OSF Preprints. November 22. doi:10.31219/osf.io/9r35j.

[5] Penfield, W. (1952). Memory Mechanisms. Archives of Neurology & Psychiatry. 67, p.p.178-198.

[6] Penfield, W., Jasper, H. (1954). Epilepsy and the Functional Anatomy of the Human Brain. Little, Brown & Company, Boston.

[7] Sutton, S. K., & Davidson, R. J. (1997). Prefrontal brain asymmetry: A biological substrate of the behavioral approach and inhibition systems. Psychological Science, 8, p.p.204–210.

[8] Schacter, D. L., & Buckner, R. L. (1998). Priming and the brain. Neuron, 20, p.p.185–195.

[9] Harris, L. T., Todorov, A., & Fiske, S. T. (2005). Attributions on the brain: Neuro-imaging dispositional inferences, beyond theory of mind. NeuroImage, 28, p.p.763–769.

[10] Pizzagalli, D. A., Sherwood, R. J., Henriques, J. B., & Davidson, R. J. (2005). Frontal brain asymmetry and reward responsiveness: A source-localization study. Psychological Science, 16, p.p. 805–813.

[11] Master, S. L., Amodio, D. M., Stanton, A. L., Yee, C. Y., Hilmert, C. J., & Taylor, S. E. (2009). Neurobiological correlates of coping through emotional approach. Brain, Behavior and Immunity, 23, p.p.27–35.

[12] Quadflieg, S., & Macrae, C. N. (2011). Stereotypes and stereotyping: What’s the brain got to do with it? European Review of Social Psychology, 22, p.p.215–273.

[13] Amodio D. M., Harmon-Jones, E., Berkman, E. (2018). Neuroscience Approaches in Social and Personality Psychology – Chapter 6 in the book “The Oxford Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology” (2 ed.), 112–150. Oxford University Press.

[14] The Enneagram Institute. How the Enneagram System Works, https://www.enneagraminstitute.com/how-the-enneagram-system-works/

[15] Chestnut & Paes Enneagram Academy. Early Childhood Relationship Patterns – Just by Knowing Enneagram Type, https://cpenneagram.com/enneagram-posts-articles/object-relations-theory-enneagram

[16] Riso, D.R., Hudson, R. (1999). The Wisdom of the Enneagram. A Bantam Book, p.76

[17] Jung C.G. (1923). Psychological Types. Pantheon Books, London (see also, CW - Collection Works, volume 6, par. 560, p.469)

[18] Riso D.R., Hudson R. (1996) Understanding the Enneagram: the practical guide to personality types. Houghton Mifflin Company, p.p. 232, 236, 251, 312.

[19] Riso D.R. with Hudson R. (1996). Personality Types. Houghton Mifflin Company, p.p.414-415.

[20] Benziger, K. (2013). Physiological and Psycho-physiological Bases for Jungian Concepts, 128 pages.

[21] Australian Centre for Leadership for Women. ACLW Leadership Interviews (2020), https://aclw.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/02-Katherine-Benziger.pdf

[22] Taylor A. Brain Models, p.3, https://www.arlenetaylor.org/images/pdfs/Brain%20Models-130724.pdf