Beyond our biological need for identity is the desire to know who we are in a deep, personal sense. Each of us maintains a self-image that is based on who we once were within our family of origin, culture and subculture.

Our self-image partially reflects how others first saw us. Therapist Salvador Minuchin has observed that “families create specialists.” That is, children often feel typecast within their family script. Early in life, we were recognized for particular qualities (“she’s sensitive, just like her grandmother”) and not others which we might also had. When we were young, our family might have needed us to play a certain role – a hero, a caretaker, a scapegoat, a peacemaker – and we took on that role in order to fit in.

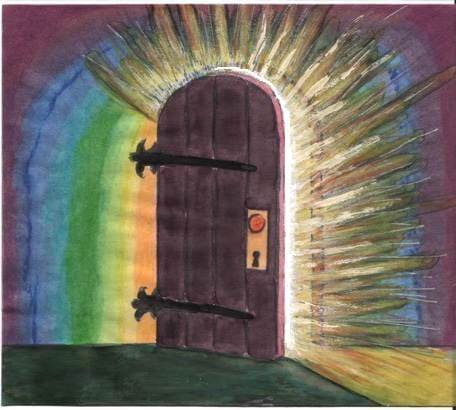

We internalized a narrow view of ourselves and began to believe it, forgetting that this view was a tactic, a defensive mask we adopted to get through childhood. Decades later we may find that the mask has stuck to our face, mistaken – even by us – for our complete identity. The goal of therapy and change work is to awaken from the dream of being only your self image.

Our self-image is deeply unconscious and attached to memories, roles, habitual emotions. It even has a body location. In the trance of our Enneagram style we are attached to our image and unconsciously believe we can’t exist without it. Some overdefended behavior is an attempt to maintain this historical image of ourselves, despite the fact that the world around us has changed.

When a Nine client of mine concentrated on his problem of being too self effacing, he saw himself as a beggar on the streets and realized that being self-effacing was an expression of this image. This is not an uncommon self-image for a Nine; many report images of peasants, refugees, bag ladies, servants or second-class citizens.

Other Enneagram styles are prone to different self-images. Ones may see themselves as prophets, reformers or arbiters of the rules, Twos as angels or helpers, Threes as high-performance success machines, Fours as unique and sensitive aliens, orphans or invalids. Fives sometimes see themselves as computers or librarians, Sixes as victims or slaves and Sevens as jesters or adventurers. Eights can see themselves as warriors or animals, especially guard dogs, sharks, and lions.

Each Enneagram trance is anchored by metaphorical self-images that drive the style’s preoccupation. The kind of self-image you have partially dictates the story you are prone to living, with all its strengths and drawbacks. An unhealthy Eight’s aggressive behavior makes more sense when you know that she subjectively lives in a jungle and has an unconscious self-image of a wild animal.

As you work on personality defenses, another kind of image that can arise is that of a child, a younger part of you who is stuck in time, fighting an old battle or coping with a difficult past circumstance. When you are overdefended, you are usually protecting something vulnerable within yourself. The unconscious often represents that vulnerability as a young self.

If I had asked my Nine client to further develop his image of a beggar, the image could have easily turned into that of a young boy. Nine children sometimes feel overlooked and unwanted and Frank’s beggar image was a metaphor for a childhood in which he felt forlorn, invisible and shy.

Other Enneagram styles have different child-images. Ones probing their defenses can discover images of children who are burdened, criticized or sad. Twos find children who are unwanted or unloved. Threes see children who are insecure or craving attention, while Fours may find children who feel rejected or privileged. With Fives, the child-images tend to be anxious, confused or ashamed. Six child-images can be pampered, helpless or terrorized. Sevens find children who are abandoned, obligated or guilty, while Eight child-images are often defenseless, betrayed or innocent.